After nine years, my people — and more than 600,000 individuals, organisations, and municipalities — are in court seeking justice against the iron ore mining company BHP. In 2015, a tailings dam collapsed close to Mariana in the state of Minas Gerais in Brazil, and we lost everything. My family, and countless others, lost our homes, our land, and our water. Our ways of life have been significantly changed. The Krenak, Pankararu and Quilombolas communities, all impacted by the disaster, are not in court seeking money. We are seeking justice. Justice that will never restore the lives, ecosystems, plants, and animals we’ve lost, nor bring back our Grandfather, our ancestral river Rio Doce, which we affectionately call Watu.

The changes that mining companies have imposed on our region have never been fair, beneficial, or welcomed by our communities. Tragedies like those in 2015, along with many other injustices, have to stop. And for that, we need to be heard.

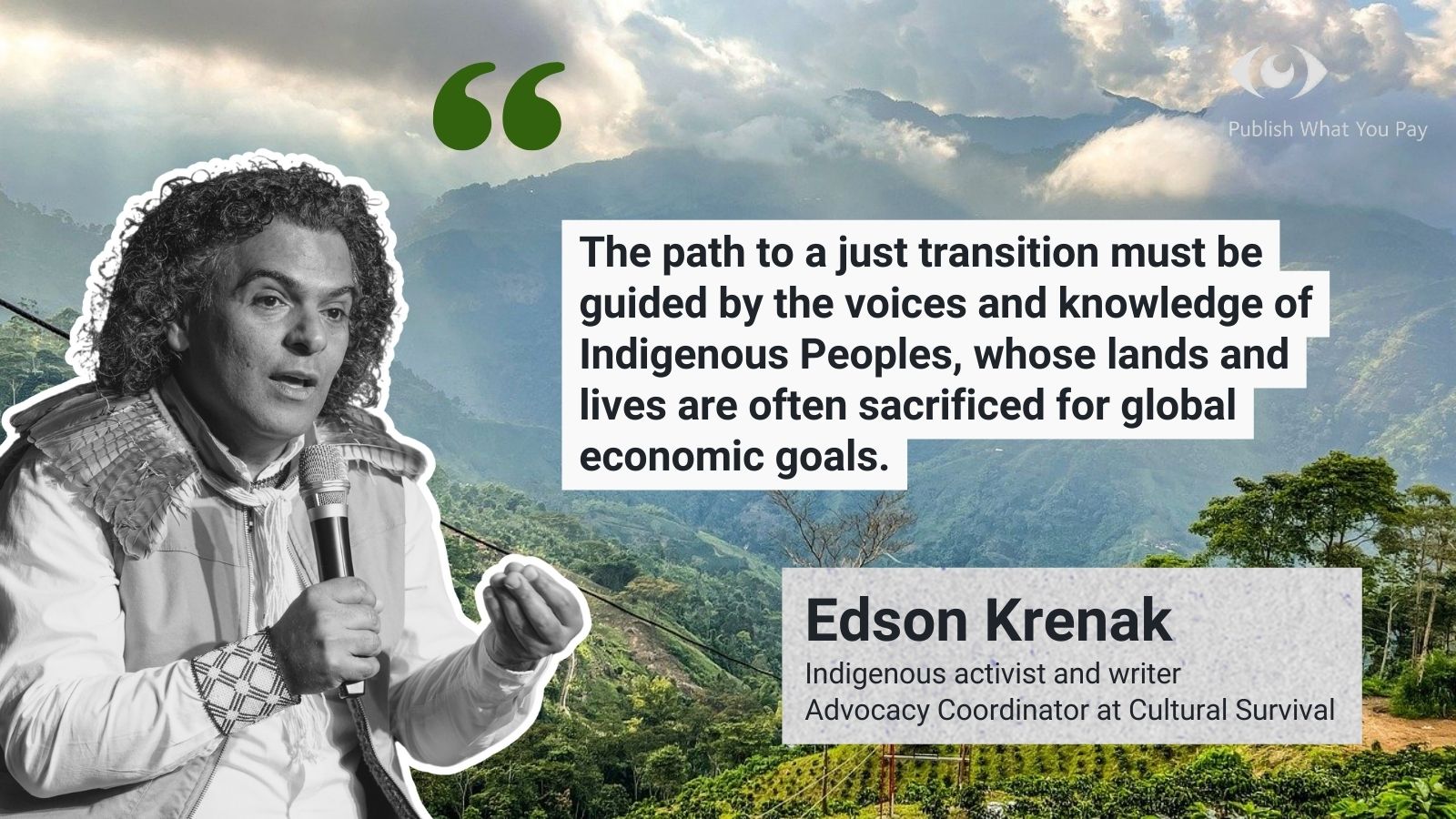

Indigenous leaders from around the world recently emphasised the urgent need to integrate Indigenous perspectives and knowledge into global energy transition strategies and developed a joint vision at a landmark summit in Switzerland. With the rising demand for transition minerals used to produce renewable energy to replace fossil fuels, this approach is essential. We need to prevent the creation of new sacrifice zones, exploited in the name of the fight against the climate crisis.

Because countries have consistently failed to protect Indigenous Peoples rights, our communities continue to be harmed by mining. Many Indigenous territories, such as the Jequitinhonha Valley in Brazil, Atacama in Chile, and Uro communities in Bolivia, are rich in transition minerals. The people living there are facing serious threats to their sacred sites, their water and their land.

For example, in the community of Piauí Poço Dantas in Itinga (Jequitinhonha Valley), where Sigma, Atlas, and CBL lithium companies operate, Djalma Gonçalves, a young man from the Aranã Caboclo people, told me that residents are experiencing respiratory issues due to lithium extraction and airborne dust. I went there and saw that houses are cracking and streets are blocked, making it difficult for ambulances and other public services to access communities. The river is dirty and dying. Djalma stated plainly: “The Jequitinhonha Valley is becoming a sacrifice zone for the green economy”.

We cannot fight the climate crisis while ignoring the social and cultural impacts of mining, such as displacement and loss of livelihoods. Indigenous advocates urge transformative action that honours Indigenous perspectives, promotes the healing of nature, and integrates environmental, social, and economic justice beyond mere resource commodification.

We demand respect of our right to say no

First, our right to Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC) must be respected. We must have the ability to grant or withhold consent to any extractive project impacting us, as guaranteed by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. In addition, self-determination, governance, cultural heritage, and land rights are essential pillars for any real solution.

Indigenous Peoples also seek active participation in decision-making processes shaping energy and environmental policies to meet climate commitments, under frameworks like the Paris Agreement.

Justice and economic policies should extend beyond financial compensation for climate-related loss and damage. Indigenous Peoples must be empowered as active agents, not passive recipients of public policies or funds, involved directly in planning and executing changes alongside decision-makers.

Although Indigenous participation in international events like COPs and OECD fora has increased, we continue to face significant challenges. Defending our lands from extractive projects often exposes us to violence, intimidation, and criminalisation. Sacred sites remain under threat due to inadequate legal protections.

A common effort to centre Indigenous knowledge in the transition

Many parts of the world such as the Jequitinhonha Valley are facing floods, droughts, and extreme heat. Current systems are focused on industrial agriculture, mining, and high consumption which continue to degrade the environment. What we need instead is a sustainable and equitable approach, fostering a new relationship with the Earth, restoring forests and protecting water sources. Indigenous knowledge is essential to guide us toward values of healing, caregiving, and sustainability. Promoting this vision must be a common effort with citizens and civil society organisations. They should:

- advocate for Indigenous peoples’ direct involvement in shaping policies, particularly transition minerals and renewable energy projects that impact their lands. This means actively including Indigenous knowledge in policy development, for example, implementing community protocols for FPIC, and designing mechanisms to ensure that Indigenous Peoples are leading the full cycle of the projects: assessment, monitoring, evaluation and benefit sharing.

- create a support network to provide legal protections, access to justice and safety for environmental defenders and Indigenous Peoples. It is time to transform promoting and enforcing legal frameworks into action plans. The Latin America and the Caribbean region can take a clear leadership role by aligning national policies with the Paris and Escazú agreements, and the Convention on Biological Diversity.

The path to a just transition must be guided by the voices and knowledge of Indigenous Peoples, whose lands and lives are often sacrificed for global economic goals. A just transition is not just about energy or economics — it is about restoring balance, respecting our cultural heritage, and safeguarding the Earth for future generations.