The most important UN panel you’ve never heard of will agree on a set of principles that could make or break the low carbon transition this week.

At stake is the future ownership of the world’s critical raw mineral supply chains that the renewable energy revolution will need to break free of our fossil fuel dependency.

The UN’s panel on critical energy transition minerals aims to inject justice, environmental standards and human rights into the sector’s supply chains. To do so, it must intervene in the international trade, investment and tax systems.

At present, the rich world wants to ensure that it – and it alone – controls critical mineral supply chains. The US Inflation Reduction Act dished out tax advantages to electric vehicle manufacturers which source, process or recycle in the US or its free trade agreement (FTA)-partners. The EU has also set a goal of processing 40% of the critical minerals that it consumes within its borders by 2030. The UK is following a similar path. But resource-rich countries aspire to process and transform more of their minerals so that they can see some of the economic rewards.

Of the ten countries which dominate the ownership of minerals via companies domiciled within their borders, eight are among the world’s richest Top 20.

While China is a major source of minerals like gallium, graphite, magnesium and tungsten, other countries including Brazil (niobium), Congo (cobalt), India (barite), Indonesia (nickel), Peru (arsenic), Russia (palladium) and South Africa (platinum and Manganese) are also significant players, and rarely talked about.

Critical minerals offer developing countries like these a “critical opportunity,” as the UN chief Antonio Guterres put it, when announcing the panel in April. “But only if they are managed properly,” he cautioned. “The race to net zero cannot trample over the poor.”

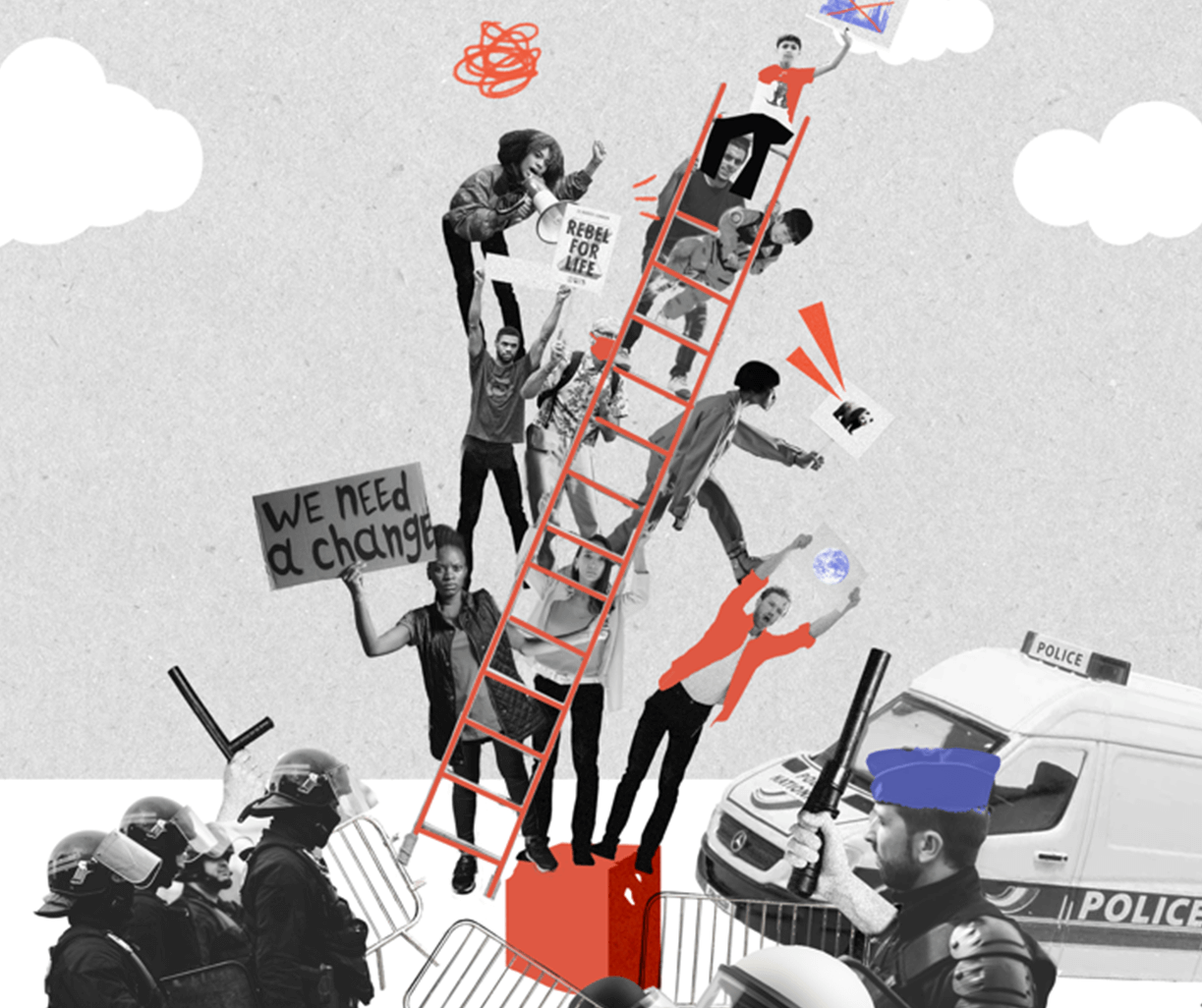

If that happens, the poor will understandably resist – and we will all suffer. To avoid this, we need a World Trade Organisation-level waiver of trade disputes in the climate realm preventing states from being challenged over policy tools crucial to sustainable industrialisation.

As well as carving producer states out of the processing value chain, the status quo also shuts out every African country except Morocco – with whom the US has an FTA – from Washington’s supply chains. This is unfair and a self-defeating invitation to other countries to strike deals with African producers, given that Africa is home to 30% of the world’s critical mineral reserves. Worse, if countries do sign FTAs, they are then prevented from adopting the same policies which could build their own green industries.

This is how it works. FTAs often prevent low and middle-income countries from using industrial policy tools – such as local content requirements, export restrictions and subsidies – to regulate, add value to, and share the benefits of their own mineral resources.

Most international investment agreements also contain investor state dispute settlement (ISDS) provisions allowing corporations to sue governments in secret arbitration panels for billions of dollars when their profit expectations are affected by measures such as environmental regulations or public health protections. Increasingly, this presents a serious disincentive to pursue industrial policies or regulate extractive projects to ensure better labour conditions or reduce environmental destruction.

Here’s an example. One Canadian-Chilean company, Tethyan Copper, won $11bn from Pakistan after the country’s supreme court ruled in favour of local communities who argued that the contract signed by a regional administration had been illegal. Tethyan had only invested $150m in exploration but its award was so large that it would have bankrupted the Pakistani state. To avoid this, Pakistan caved in and awarded Tethyan a mining license.

ISDS mechanisms are a holdover from attempts to prevent former colonies from appropriating industrial concerns after independence. The office of the US trade representative compared them to gunboat diplomacy, while other liken the campaign against ISDS to abolishing slavery. The truth is that ISDS has no place in the modern world and should be repudiated and renegotiated by all nations working in this sector.

The world must also move to prevent a race to the bottom in tax competition. Fair taxation that allows for sustained industrialisation is essential for long term fiscal stability and high value chain integration. Disclosure requirements, the cross-border exchange of tax information to counter evasion threats and integrated regional partnerships can all build transition mineral value chains into a sustainable regional development model.

Ultimately, if we don’t get this right, the green transition will look – to most in the world – like just another resource grab. The green transition must be redistributive in order to have the global buy-in to succeed.

But to do this effectively at the scale needed, it will be necessary to go beyond the UN panel. Perhaps we need to start thinking about a producer organisation similar to the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (Opec) in the 1970s, which advanced the interests of critical resource producers in a very different time, and context. Certainly, the distribution of critical mineral profits should be fairer, the environmental impacts should be more closely monitored, and the democratic control of the sector’s decision-making processes must be broader and deeper.

In the teeth of a global economic system that answers first to the call of the dollar, it seems that it may well be time for producers to take a stand together. To quote Guterres again: “The renewables revolution is happening, but we must guide it towards justice.”