In 1994, Illicit Financial Flows (IFFs) were a major threat to South Africa’s development agenda. Today, Africa’s huge external debt problem can be partially blamed on lost revenue due to illicit flows. A United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) report noted that Africa’s external debt stood at $279 billion in 2008 and that debt constituted a third of the amount lost to IFFs at that time.

Yet how do we define Illicit Financial Flows and what can be done to tackle this growing issue?

It is important to look at how the problem is defined and how we can understand the causes and the solutions to this. Poorly defined IFFs can lead to measures which waste resources without achieving the intended impact.

Most definitions of IFFs by the World Bank Group (WBG), the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the Global Financial Integrity (GFI) have one common thread: the illegal nature of IFFs activities. GFI defines IFFs as money that is illegally earned, transferred or used across borders. The WBG considers the illegality of IFFs if they are in violation with the laws of the country of origin.

The strength of defining IFFs through the prism of illegal activities gives room to focus on solutions that are steeped in administrative efficiency in terms of enforcing compliance as well as reviewing of legislation.

“Clearly the varying estimates carry one important message: amounts involved are quite substantial and pose a huge roadblock to Africa’s development agenda”

It is also interesting to look at the IFFs definition from the High Level Panel report known as the Mbeki report. Tax avoidance, though not deemed illegal but against the spirit of the law, is an added feature to the illegal activities in this particular definition of IFFs.

The Mbeki report was endorsed by African heads of states, a signpost that IFFs are a major threat to Africa’s development initiatives. The Third Conference on Finance for Development held in Addis Ababa in 2015 also conceded that IFFs pose a major risk to development and measures must be put in place to mitigate and stop the illicit flows by 2030.

Likewise, the amount of funds lost due to IFFs varies depending on the source. UNECA, for instance, estimates that Africa is losing $50 billion annually. Significantly, focus should not be on the varying IFFs estimates. Clearly the varying estimates carry one important message: amounts involved are quite substantial and pose a huge roadblock to Africa’s development agenda.

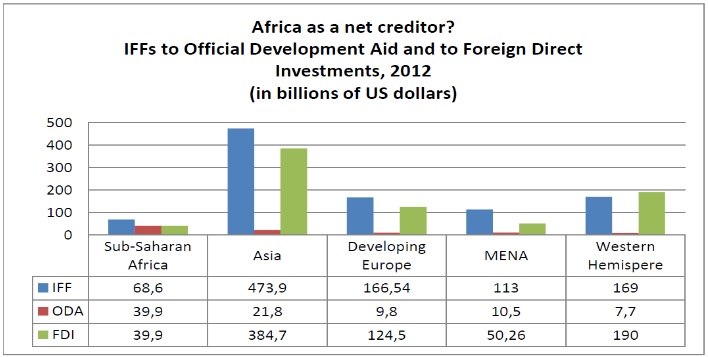

Official Development Assistance (ODA) and Foreign Direct Investments (FDIs), traditional known anchors of development finance, are dwarfed by IFFs as illustrated in the table below:

There is a causal relationship between IFFs and lost social and infrastructure investment opportunities. However, this relationship must not detract from the necessity of analysis. If past and current public investments are transparent and efficient, curbing IFFs will yield the intended results. In other words, the focus on IFFs should not overshadow the work that drives efficient public investments.

IFFs also give an unfair advantage to companies who enjoy the use of public infrastructure which they are not keen to finance through payment of taxes to government. Inequality is perpetuated and worsened by IFFs, and small to medium enterprises and consumers bear the disproportionate burden of taxation.

Although IFFs strip revenue through illegal activities such as tax evasion and not-so-illegal but nonetheless immoral tax avoidance strategy, resource-rich countries are essentially stripping themselves of taxation rights through harmful tax incentives.

The discussion on revenue leakages should therefore not solely pivot on IFFs but should also consider the impact of harmful tax incentives. After all, ending harmful tax incentives can be much easier than stopping IFFs. There is a need to disclose the cost of tax incentives as part of fiscal transparency, and countries such as Burkina Faso have started doing just that.

On governance issues, transparency is consdiered a vital cog in the fight against corruption and IFFs. No wonder the extractive sector, with its well-known opaqueness, is hit hardest by IFFs. More transparency leads to accountability and better management of the sector. This is what drives the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI).

Overall, citizens must drive the agenda of policy and practice reforms to curb the illicit flows. Civil Society Organisations have a duty galvanise aggregate citizens’ demand for accountability from governments and companies on actions against IFFs. If the government is interested in curbing IFFs, it can recoup much needed revenue to fund social and infrastructure programmes. Companies stand to gain from stemming IFFs once the cost of doing business is lowered and long-term investments can be made possible due to a stable investment climate.