Transparency’s next frontier – Why extractive industry procurement should be a focus of civil society

Blogs and News

It is remarkable how far the global movement for transparency in extractive industries has come. The Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) is now at fifty-five member countries, and civil society has successfully pressured governments in the United Kingdom, Europe, and Canada to adopt laws requiring their headquartered mining and oil and gas companies report revenue payments made to governments in any country where they operate.

For mining however, it may be a surprise to many civil society organisations that in terms of dollars spent, in virtually all cases a mine site spends much more money in host countries on the procurement of goods and services than taxes.

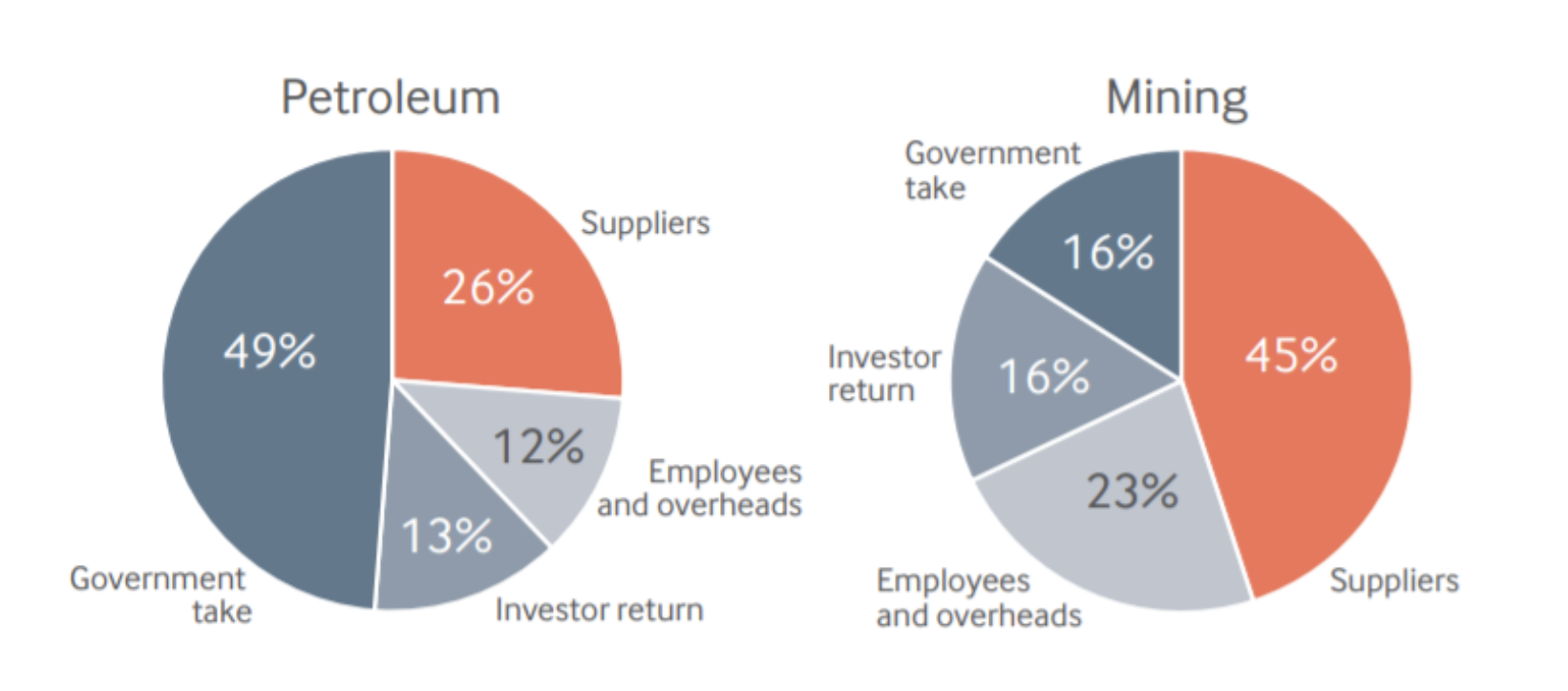

Figure 1: Natural Source Governance Institute’s estimate distribution of gross revenues generated by extractive industries, cumulative 2000 to 2017, Beneath the Surface: The Case for Oversight of Extractive Industry Suppliers, p. 5

The Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI) estimates 45% of all revenue spent by mining companies goes to suppliers globally. When looking at in-country spending by mining companies, this figure rises even higher, and for example the World Gold Council found that in 2013 across its member companies, 71% of all payments made in country went to suppliers.

In oil and gas production, governments take a higher share of overall revenues spent by producer companies, but given the scale of overall activity is so much higher, that 26% going to suppliers represents much larger spending in dollar figures. Overall the NRGI estimated that nearly one trillion dollars each year was spent by mining and oil and gas companies on suppliers from 2018 to 2017.

For the mining sector, our focus at Mining Shared Value, a typical large-scale mine site will spend hundreds of millions of dollars (US) each year for all the inputs it needs.

Not all of this spending on procurement of goods and services is going to be on locally manufactured goods or services supplied by locally owned and managed firms. With hundreds of millions being spent each year however, this shows that even small shifts in procurement spending can result in millions of dollars staying closer to the mine site.

Procurement spending by mining companies is therefore an important opportunity for host countries to achieve meaningful economic and social benefits from mining activity – if governed well.

Conversely, while this huge spending can propel meaningful economic growth and skills building, procurement by extractive industry companies can also be a major risk for corruption and other problematic practices. Businesses can bribe extractive industry companies to secure contracts for example, or a mining company can use procurement as a means of paying bribes to government officials.

For a very good illustration of this risk, one can examine the Operação Lava Jato (Operation Car Wash) scandal in Brazil. In this scandal, executives of the state-owned oil company Petrobras allegedly accepted bribes from businesses and in exchange awarded contracts to the construction firms providing cash, at inflated prices.

In Beneath the Surface: The Case for Oversight of Extractive Industry Suppliers, the NRGI reviewed over 40 extractive industry corruption cases, and found examples where suppliers were actors in the abuses in at least twenty-nine countries across five continents.

This potential for great economic benefit from extractive industry procurement, and at the same time this major risk for corruption, means we need more transparency in the way in which mining and oil and gas companies procure goods and services.

This is why in 2017 with our partners at GIZ we launched the Mining Local Procurement Reporting Mechanism (LPRM), which is a set of disclosures to increase and standardise how mine sites report on their procurement policies, processes and ultimately how much spending is going to host country suppliers.

As of October 2021, there are now nine mining companies using the LPRM, reporting on twenty-three sites across thirteen countries.

While targeted at the mining sector, the disclosures are for the most part equally applicable for the oil and gas sector, and in fact the EITI in Senegal is already using several of the LPRM’s disclosures in their information requests from oil and gas companies, in addition to those in mining.

Now we are working with civil society organisations around the world to support them to understand the high stakes of mining sector procurement, and how they can push for more transparency.

In partnership with Publish What You Pay and with the support of OSIWA, we were excited to recently launch Promoting Backward Linkages and Transparency: A Civil Society Guide to the Mining Local Procurement Reporting Mechanism.

This guide explains the huge scale of procurement by the mining sector, introduces the Mining LPRM, and provides practical ideas for CSOs to use to advocate companies and governments to adopt the Mining LPRM.

We are also working directly with CSOs and their networks on capacity-building initiatives as well. The guide itself was created as part of the Publish What You Pay project in West Africa funded by OSIWA, introducing the LPRM to coalitions in Mali, Cote d’Ivoire, Niger, and Guinea. Capacity-building workshops have been held and more will occur in 2022.

In Latin America we recently began working with CSOs in Colombia and Peru in a new project supported by the Ford Foundation. The aim is to build the capacity of organisations working on extractive industry governance to advocate for transparent procurement by the mining sector.

As civil society we have come so far to make extractive industry activity more transparent in order to help improve the outcomes for host countries. We are excited to work with all of you to keep pushing the frontiers of transparency even further and hopefully achieve similar progress when it comes to the procurement of goods and services.

Jeff Geipel

Managing Director, Mining Shared Value

Engineers Without Borders Canada