Zimbabwe, like many other mineral rich developing countries, isn’t seeing many benefits from the extraction of its mineral wealth. In fact, in 2015, Zimbabwe lost $500 million according to the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ). Moreover, Africa is losing as much as $50 billion per annum to illicit financial flows. These dramatic numbers show that there is wrong with the current system. But the recent Panama Papers have presented additional vital, albeit piecemeal, evidence that further expose how the flow of mineral revenue is skewed in favour of private interests. This rigged system hinders much needed investment for the improvement of the living standards of many citizens of Zimbabwe and of those of other poor but resource rich countries.

The fact that allegedly dirty dealings by Zimplats, one of the country’s largest mines, were exposed through the recent Panama leaks does not mean that other mining companies operating in Zimbabwe are in the clear. Rather, the Zimplats saga shows just how high the risk of tax evasion is in the entire mining sector, particularly when Multi-National Corporations (MNCs) are involved. It is important to point out that Zimplats has refuted the allegations by distancing itself from HR Consultancy, the firm behind the illegal payment of Zimplats’ senior employees.

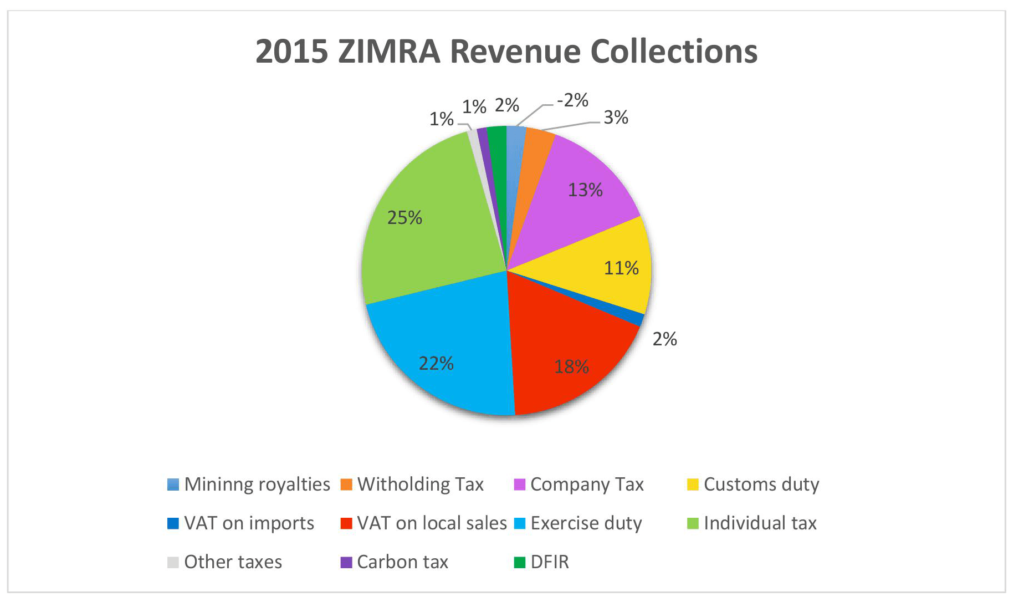

Zimplats supposedly dodged payroll related taxes by using an offshore company to pay millions of dollars to its senior employees over a number of years. Payroll related taxes, commonly referred to as Pay As You Earn (PAYE), dominate the Individual tax head which is one of the lead revenue streams to the treasury as highlighted by the chart below.

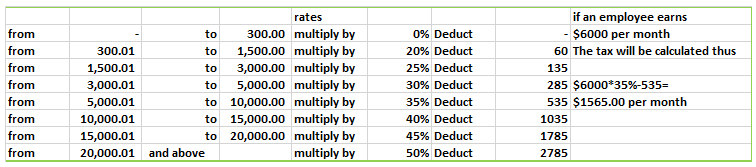

A peek at the Zimbabwe Revenue Authority’s (ZIMRA) 2015 PAYE tax table below shows a progressive payroll scheme in which those that earn more are supposed to pay more. However, when income is shifted from the countries where resources are extracted to tax havens like Panama, progressive tax rules become essentially regressive. The poor end up shouldering an unfair share of the tax burden whilst the rich find ways to avoid paying their fair share.

Illicit Financial Flows (IFFs) are not limited to loss of tax revenue. IFFs also deflate export revenue which contribute to the liquidity crisis currently affecting Zimbabwe. With the mining sector accounting for over 50% of Zimbabwe’s total exports earnings, the impact of IFFs cannot be overemphasised.

Apart from tax evasion and tax avoidance, harmful tax incentives from secretive and weak mining agreements are undermining the mining sector’s contribution to the state coffers. The Zimplats payroll story as revealed by the Panama leaks comes at the backdrop of Zimbabwe’s negative 113.30% mineral royalty performance in 2015 in which Zimplats was also involved. From the initial national annual royalty target of approximately $146 million, there was instead a negative balance of $19.4 million.

If developed countries with reputably strong institutions are affected by tax evasion as shown by the Panama Papers, the impact on countries with weak institutions such as Zimbabwe is very concerning. The Panama Papers have partly perforated the veil of secrecy that camouflages global financial transactions through tax havens, consequently exacerbating income inequality. They strengthen the case for the international financial architecture to be reformed in order to yield greater transparency. This will arm resource-rich countries with data to plug leakages and allow them to track lost revenue.

The Panama Papers present an opportunity which Zimbabwe must not waste. Lost revenue must be tracked and recovered and the culprits must be accountable so that a heavy blow is dealt to IFFs. The Panama Papers leaks come as a stark reminder that Zimbabwe must not be left behind in critical mineral transparency reforms including beneficial ownership which is an important piece to the puzzle of solving corruption. It is sad to note that the country lacks institutionalised revenue transparency which could help boost the role of mineral wealth in development as intentioned by the country’s year economic blue print. That is, the Zimbabwe Agenda for Sustainable Socio Economic Transformation (Zim-Asset 2013-2018).