Making women visible and locating gender expertise in their own movements have put West African Publish What You Pay (PWYP) coalitions at the forefront of working with gender in extractives. But there is a long journey ahead before minds and work processes have shifted to more gendered ways of working.

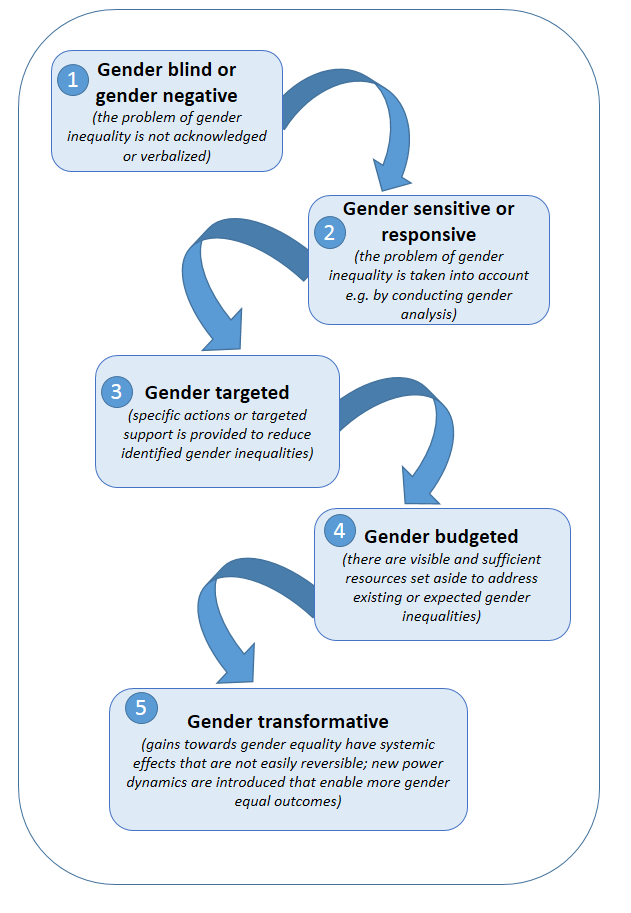

How do you change a system that is largely ‘gender blind’? That is, if women are systematically underrepresented or absent from discussions, if gender is not on the agenda, and if women are made even more invisible by not gender disaggregating routinely collected data and using it for analysis.

For many (if not most) civil society groups seeking to influence the transparent governance of extractive industries in their countries, this is a reality. And it led to PWYP picking up the challenge to undertake some research, led by three PWYP coalitions in West Africa (Burkina Faso, Guinea and Senegal), with others joining (Ghana, Nigeria and Togo) to do a gender scan of their own coalitions and membership. These gender scans sought to answer: Where do women and men currently participate in our system? Where are there gender disparities and why? And where is there existing gender expertise among our members that we can collectively draw on?

For many (if not most) civil society groups seeking to influence the transparent governance of extractive industries in their countries, this is a reality. And it led to PWYP picking up the challenge to undertake some research, led by three PWYP coalitions in West Africa (Burkina Faso, Guinea and Senegal), with others joining (Ghana, Nigeria and Togo) to do a gender scan of their own coalitions and membership. These gender scans sought to answer: Where do women and men currently participate in our system? Where are there gender disparities and why? And where is there existing gender expertise among our members that we can collectively draw on?

Gender ‘neutrality’ solidifies status quo

A wealth of literature points to inherent gender inequalities in the extractives sector, with benefits and risks unfairly shared. Consequently, gender blind policies and data (until recently considered ‘gender neutral’) actually create negative gender outcomes for women by helping to maintain, or further aggravate, existing power imbalances while failing to support women as a force for development.

Other factors may also play in. A predominantly male culture can make informal ‘pat-on-the-back deals’ between men more acceptable. To thrive in this culture, women may have to adjust to it rather than using their voice to express solidarity with more marginalized women. All this affects transparency, as exemplified across the PWYP coalitions’ reports.

Recently the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) has been more vocal on gender issues. However, it is up to EITI implementing countries to put a more transformative gender approach into practice. So far, much has remained aspirational, and a previous PWYP blog argues that women have largely been left behind. Three key takeaways from the West African gender research are synthesized below:

- Make women – and gender disparities – visible

It’s easy to accept status quo for as long as women are mostly invisible and gender issues are not systematically analyzed. At present that is the case. A gender break-down of participation in governance and decision-making structures within the EITI universe is not easily available; neither is it always clear what percentage of participants were women or representing local women’s groups when validations of EITI reports took place locally.

Multi-stakeholder groups (MSGs) – with representatives from government, companies and civil society mandated to oversee the national EITI implementation – had a representation of women which varied from 7% to 20%. Some MSGs elsewhere have no women participating at all according to research by the Institute for Multi-stakeholder Initiative Integrity (2015).

Another form of making women invisible is not gender disaggregating data in the reporting. When it exceptionally happens, reported gender disparities are revealing. For instance, in Burkina Faso the 2016 EITI report showed that women held less than 3% of all jobs created by mining companies (with no further analysis included, or contextualized information from women’s groups on the ground). Moreover, a cross-country comparison is not possible since up until now, gender disaggregation of data is not required according to the EITI Standard.

- Make gender issues discussed and acted upon

But lopsided participation is only one side of the story. The sometimes astonishingly low level of participation of women in EITI processes is often symptomatic of broader, deeper, more structural gender inequalities and power imbalances. These need to be analyzed holistically, with a wider-angle gender lens.

Several of the coalition research reports found glaring gaps between the relatively good national policy framework for advancing gender equality (e.g. via national gender plans and strategies), and the complete absence of any references to gender in the frameworks regulating extractive industries. Local women’s groups as well as national public institutions mandated to promote gender equality (such as the Gender Ministry, the gender unit in the Ministry of Planning etc.) could play an important role in making such linkages clearer, with PWYP potentially helping to broker such knowledge.

Each of the participating PWYP coalitions could identify at least a few members with particularly relevant gender expertise. While some of them had previously been relatively inactive in the coalition, the ‘buzz’ of doing this research led to increased interest, with a few additional gender-focused groups wanting to join as members.

- Get gender into the institutional DNA and culture

As part of the research, we developed a method for visualizing and tracking gender references across key documents (work plans, strategic plans, reporting etc.) to determine whether gender really was part of the institutional DNA or whether it was just mentioned in passing. Any reference (or dedicated publication) on gender issues was either classified as: aspirational – meaning that it constituted a recommendation or non-obligatory guidance, but had not yet happened; normative – indicating some sort of obligation (e.g. in a Code of Conduct); informational – stating a fact, announcing upcoming gender-focused events or providing a gender break-down of participation; results-oriented – accounting for gendered impacts or results (including analysis of such results); and community generated – representing feedback and data from those who are closest to the problem on the ground.

Even though coalitions often reported a complete absence – or at best aspirational or informational – gender references in key documents at this point, the idea is to continue to use this classification to track how it might evolve over time. It could also be a way to hold each other mutually to account for incorporating a gender dimension in the EITI multi-stakeholder partnership.

In conclusion, isolated gender projects like this one clearly cannot do the job of gender mainstreaming the broader EITI process on its own. Nevertheless, this research – as part of a longer PWYP gender project funded by the Hewlett Foundation – can maybe be a first trigger. In addition to taking stock and providing a baseline, it illustrates how women are not just potential victims or passive beneficiaries of extractive resources or economic opportunities in the sector; they are also forceful change makers. That is when they are not excluded, and when deeper gender inequalities are not ignored.

A gendered approach to transparently governed extractive industries may still be a distant destination, but at least in West Africa, the navigation for how to get there has started.